Sandow

Registered

Ever-rising premiums have pushed some to drop coverage

The cost of family health coverage in the U.S. now tops $20,000, an annual survey of employers found, a record high that has pushed an increasing number of American workers into plans that cover less or cost more, or force them out of the insurance market entirely.

“It’s as much as buying a basic economy car,” said Drew Altman, chief executive officer of the Kaiser Family Foundation, “but buying it every year.” The nonprofit health research group conducts the yearly survey of coverage that people get through work, the main source of insurance in the U.S. for people under age 65.

While employers pay most of the costs of coverage, according to the survey, workers’ average contribution is now $6,000 for a family plan. That’s just their share of upfront premiums, and doesn’t include co-payments, deductibles and other forms of cost-sharing once they need care.

The seemingly inexorable rise of costs has led to deep frustration with U.S. health care, prompting questions about whether a system where coverage is tied to a job can survive. As premiums and deductibles have increased in the last two decades, the percentage of workers covered has slipped as employers dropped coverage and some workers chose not to enroll. Fewer Americans under 65 had employer coverage in 2017 than in 1999, according to a separate Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of federal data. That’s despite the fact that the U.S. economy employed 17 million more people in 2017 than in 1999.

“What we’ve been seeing is a slow, slow kind of drip-drip erosion in employer coverage,” Altman said.

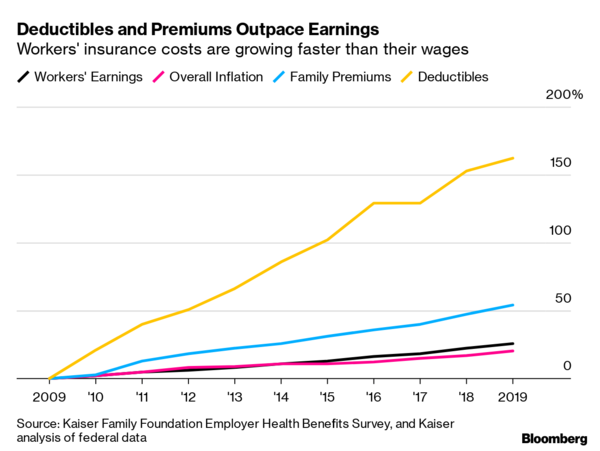

Employees’ costs for health care are rising more quickly than wages or overall economy-wide prices, and the working poor have been particularly hard-hit. In firms where more than 35% of employees earn less than $25,000 a year, workers would have to contribute more than $7,000 for a family health plan. It’s an expense that Altman calls “just flat-out not affordable.” Only one-third of employees at such firms are on their employer’s health plans, compared with 63% at higher-wage firms, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s data.

The survey is based on responses from more than 2,000 randomly selected employers with at least three workers, including private firms and non-federal public employers.

Deductibles are rising even faster than premiums, meaning that patients are on the hook for more of their medical costs upfront. For a single person, the average deductible in 2019 was $1,396, up from $533 in 2009. A typical household with employer health coverage spends about $800 a year in out-of-pocket costs, not counting premiums, according to research from the Commonwealth Fund. At the high end of the range, those costs can top $5,000 a year.

While raising deductibles can moderate premiums, it also increases costs for people with an illness or who get hurt. “Cost-sharing is a tax on the sick,” said Mark Fendrick, director of the Center for Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan.

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover certain preventive services such as immunizations and annual wellness visits without patient cost-sharing. But patients still have to pay out-of-pocket for other essential care, such as medication for chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure, until they meet their deductibles.

Many Americans aren’t prepared for the risks that deductibles transfer to patients. Almost 40% of adults can’t pay an unexpected $400 expense without borrowing or selling an asset, according to a Federal Reserve survey from May.

That’s a problem, Fendrick said. “My patient should not have to have a bake sale to afford her insulin,” he said.

After years of pushing health-care costs onto workers, some employers are pressing pause. Delta Air Lines Inc. recently froze employees’ contributions to premiums for two years, Chief Executive Officer Ed Bastian said in an interview at Bloomberg’s headquarters in New York last week.

“We said we’re not going to raise them. We're going to absorb the cost because we need to make certain people know that their benefits structure is real important,” Bastian said. He said the company’s health-care costs are growing by double-digits. The Atlanta-based company has more than 80,000 employees around the globe.

Some large employers have reversed course on asking workers to take on more costs, according to a separate survey from the National Business Group on Health. In 2020, fewer companies will limit employees to so-called “consumer-directed health plans,” which pair high-deductible coverage with savings accounts for medical spending funded by workers and employers, according to the survey. That will be the only plan available at 25% of large employers in the survey, down from 39% in 2018.

Employers have to balance their desire to control costs with their need to attract and keep workers, said Kaiser’s Altman. That leaves them less inclined to make aggressive moves to tackle underlying medical costs, such as by cutting high-cost hospitals out of their networks. In recent years employers’ health-care costs have remained steady as a share of their total compensation expenses.

“There’s a lot of gnashing of teeth,” Altman said, “but if you look at what they do, not what they say, it’s reasonably vanilla.”

Published by Bloomberg

The cost of family health coverage in the U.S. now tops $20,000, an annual survey of employers found, a record high that has pushed an increasing number of American workers into plans that cover less or cost more, or force them out of the insurance market entirely.

“It’s as much as buying a basic economy car,” said Drew Altman, chief executive officer of the Kaiser Family Foundation, “but buying it every year.” The nonprofit health research group conducts the yearly survey of coverage that people get through work, the main source of insurance in the U.S. for people under age 65.

While employers pay most of the costs of coverage, according to the survey, workers’ average contribution is now $6,000 for a family plan. That’s just their share of upfront premiums, and doesn’t include co-payments, deductibles and other forms of cost-sharing once they need care.

The seemingly inexorable rise of costs has led to deep frustration with U.S. health care, prompting questions about whether a system where coverage is tied to a job can survive. As premiums and deductibles have increased in the last two decades, the percentage of workers covered has slipped as employers dropped coverage and some workers chose not to enroll. Fewer Americans under 65 had employer coverage in 2017 than in 1999, according to a separate Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of federal data. That’s despite the fact that the U.S. economy employed 17 million more people in 2017 than in 1999.

“What we’ve been seeing is a slow, slow kind of drip-drip erosion in employer coverage,” Altman said.

Employees’ costs for health care are rising more quickly than wages or overall economy-wide prices, and the working poor have been particularly hard-hit. In firms where more than 35% of employees earn less than $25,000 a year, workers would have to contribute more than $7,000 for a family health plan. It’s an expense that Altman calls “just flat-out not affordable.” Only one-third of employees at such firms are on their employer’s health plans, compared with 63% at higher-wage firms, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s data.

The survey is based on responses from more than 2,000 randomly selected employers with at least three workers, including private firms and non-federal public employers.

Deductibles are rising even faster than premiums, meaning that patients are on the hook for more of their medical costs upfront. For a single person, the average deductible in 2019 was $1,396, up from $533 in 2009. A typical household with employer health coverage spends about $800 a year in out-of-pocket costs, not counting premiums, according to research from the Commonwealth Fund. At the high end of the range, those costs can top $5,000 a year.

While raising deductibles can moderate premiums, it also increases costs for people with an illness or who get hurt. “Cost-sharing is a tax on the sick,” said Mark Fendrick, director of the Center for Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan.

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover certain preventive services such as immunizations and annual wellness visits without patient cost-sharing. But patients still have to pay out-of-pocket for other essential care, such as medication for chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure, until they meet their deductibles.

Many Americans aren’t prepared for the risks that deductibles transfer to patients. Almost 40% of adults can’t pay an unexpected $400 expense without borrowing or selling an asset, according to a Federal Reserve survey from May.

That’s a problem, Fendrick said. “My patient should not have to have a bake sale to afford her insulin,” he said.

After years of pushing health-care costs onto workers, some employers are pressing pause. Delta Air Lines Inc. recently froze employees’ contributions to premiums for two years, Chief Executive Officer Ed Bastian said in an interview at Bloomberg’s headquarters in New York last week.

“We said we’re not going to raise them. We're going to absorb the cost because we need to make certain people know that their benefits structure is real important,” Bastian said. He said the company’s health-care costs are growing by double-digits. The Atlanta-based company has more than 80,000 employees around the globe.

Some large employers have reversed course on asking workers to take on more costs, according to a separate survey from the National Business Group on Health. In 2020, fewer companies will limit employees to so-called “consumer-directed health plans,” which pair high-deductible coverage with savings accounts for medical spending funded by workers and employers, according to the survey. That will be the only plan available at 25% of large employers in the survey, down from 39% in 2018.

Employers have to balance their desire to control costs with their need to attract and keep workers, said Kaiser’s Altman. That leaves them less inclined to make aggressive moves to tackle underlying medical costs, such as by cutting high-cost hospitals out of their networks. In recent years employers’ health-care costs have remained steady as a share of their total compensation expenses.

“There’s a lot of gnashing of teeth,” Altman said, “but if you look at what they do, not what they say, it’s reasonably vanilla.”

Published by Bloomberg